The coronavirus crisis has Americans hoarding more money than ever as widespread fear paralyzes consumer spending habits.

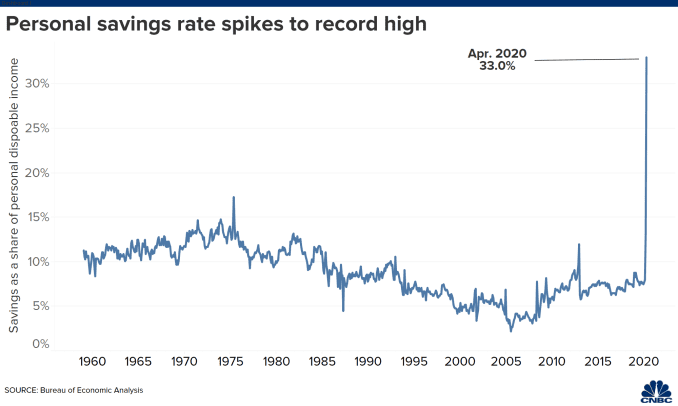

The personal savings rate hit a historic 33% in April, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis said Friday. This rate — how much people save as a percentage of their disposable income — is by far the highest since the department started tracking in the 1960s. April’s mark is up from 12.7% in March.

The swiftness and severity of a U.S. economic recovery hinges on whether consumers continue to stockpile cash or start to spend again.

“There is a tremendous uncertainty and virus fear that is lingering, and that is restraining people’s desire to go out and spend as they normally would,” said Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics.

The previous record savings rate was 17.3% in May 1975, according to FactSet. The savings rate was elevated above 13% throughout most of the early 1970s. The increase in savings came as spending declined by a record 13.6% in April.

U.S. consumers have amassed savings as the deadly coronavirus causes unprecedented economic and societal disruption. The deadly virus — which forced a government mandated shutdown of the economy — has caused more than 40 million Americans to file for unemployment since the virus was declared a pandemic.

“The saving rate is the residual of an extraordinary event,” Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton, told CNBC.

With the U.S. consumer accounting for more two-thirds of the economy, the speed and robustness of economic recovery depends on whether the increase in savings is a result of the shutdown or reflects a more structural change in consumer habits, analysts told CNBC.

‘Forced savings’

Saving during the Covid-19 pandemic is especially unique due to the shutdowns. Hundreds of thousands of small and large businesses shuttered their doors in an effort to curb the fast-spreading virus.

There is an aspect of “forced savings,” said Swonk.

“There’s not much opportunity for many people to go out and spend money,” said Megan Greene, a senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School. “With shops all closed and everybody locked up, the ‘shopportunities’ have dried up. That speaks to a kind of demand shock.”

On the other hand, a more structural change in saving and spending habits with “scarring” in consumers can have intense repercussions for the economy. This occurred during the Great Recession and can exacerbate secular stagnation, which “keeps interest rates and growth and inflation all low for a long time,” said Greene.

“As long as the money is put in savings instead of being invested, then typically that tends to weigh on interest rates, it tends to curb growth and to weaken the potential of the economy,” Daco said.

During a crisis or a recession it is entirely rational for an individual to be more conservative with their spending and savings, said Marc Odo, portfolio manager at Swan Global Investments.

“The paradox is that if everyone across the broad economy is hunkering down, that only makes the recession worse,” Odo said. “The paradox of thrift is a negative feedback loop. The more people save, the less they spend; the less they spend, the worse the recession gets; the worse the recession gets the more they save.”

Consumer spending habits will play a large roll in whether the economy recovers in a V shape, a W shape or a swoosh.

Leave a Reply